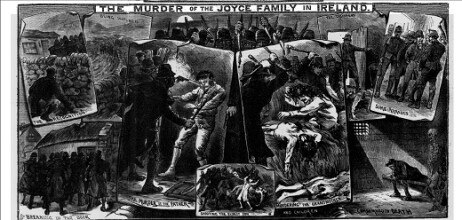

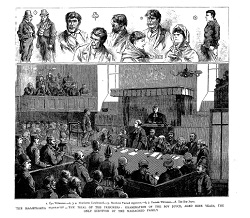

Two new books, a docu-drama, and a presidential pardon, have brought the late nineteenth-century Maamtrasna murder case back to public prominence in recent years. The incidents they describe began on 17 August 1882, with the murder of five family members in Maamtrasna, Co. Galway. Eight men were tried and convicted, on the basis of perjured testimony. Three of them were executed and the others imprisoned for life. Two of the convicted prisoners and two informers later admitted the innocence of Maolra Seoighe (Myles Joyce), who had been put to death. In 2018 on the advice of government, President Michael D. Higgins formally pardoned Seoighe. Part of the injustice was the fact that the trial took place in English, with only a very limited interpretation service provided to the defendants, who were primarily monoglot Irish speakers.

The book by former Irish language commissioner Seán Ó Cuirreáin, Éagóir (2016), began this new attention (itself taking inspiration from Jarlath Waldron’s 1992 Maamtrasna: The Murders and the Mystery), followed by Ciarán Ó Cofaigh’s feature-length docu-drama based on Ó Cuirreáin’s work, Murdair Mhám Trasna (broadcast on TG4 in April 2018). Margaret Kelleher’s prize-winning The Maamtrasna Murders: Language, Life and Death in Nineteenth-Century Ireland (2018), is the most recent study, drawing on new archival research.

As a lecturer in Irish, the case has long interested me. In 2008, while teaching at NUI Galway for the BA in Irish, I worked closely with Seán Ó Cuirreáin to develop appropriate teaching materials to make a complex and demanding topic accessible and interesting to the average contemporary student not prone to excessive background research or engagement – a tall order, you might say. Getting students of Irish to brainstorm what might be meant by language rights was difficult as only the small minority who come from what might be described as activist backgrounds had ever given it any consideration.

Seán was researching his book on Maamtrasna at the time and suggested that I include James Joyce’s journalistic commentary from 1907 on the hanging of Maolra Seoighe, an article published in an Italian newspaper when Joyce was living in Trieste. Although Joyce’s account contains many historical inaccuracies, it is nonetheless an arresting and jolting reflection on the sheer injustice done to the three men who were hanged outside Galway Jail in 1882. Reading this aloud in class at the start of every academic year has never ceased to be moving both for me and students:

When the questioning was over, the guilt of the poor old man was declared proved, and he was remanded to a superior court which condemned him to the noose. On the day the sentence was executed, the square in front of the prison was jammed full of kneeling people shouting prayers in Irish for the repose of Myles Joyce’s soul. The story was told that the executioner, unable to make the victim understand him, kicked at the miserable man's head in anger to shove it into the noose.

The classroom discussion that follows almost inevitably reveals a sense of awakening among students about the issue of language rights, how they could literally be a matter of life or death in late nineteenth-century Ireland and how they continue to be relevant today. I’m not claiming credit for turning out a revolutionary cadre every year – although that wouldn’t be a bad thing – but I don’t believe that it is possible to study a minoritised language such as Irish without considering the pressures on its speakers, something never considered by monolingual speakers of hegemonic languages. As Margaret Kelleher so eloquently puts it, this involves recognising the ‘processes of attempted usage, prohibition and the failure to be heard’. The erasure or the silencing of speakers of minoritised languages such as Irish continues to resonate today, and is at heart of the study of the links between language ideologies and language practices.

And that leads me to the relevance of the stories told by Seán Ó Cuirreáin, Margaret Kelleher, Ciarán Ó Cofaigh, and others before them for the contemporary study of the sociolinguistics of Irish. They provide a crucial historical context for the contemporary study of language rights, language legislation and the revitalisation of minoritised languages in general. I welcome Margaret Kelleher’s use of critical sociolinguistics to throw light on the conceptual deficiencies inherent in long-standing linguistic categories such as ‘language’, ‘bilingual’ and ‘multilingual’ and her attention to the ‘messiness’ of sociolinguistics and language shift itself, as Monica Heller and other scholars of sociolinguistics have characterised it.

Published: 5 Jun 2019 Categories: Cultural Studies, History, Irish Literature, Literary Theory