The language surrounding disability changes over time. There are certain terms which were previously common for describing disabled people but would now be considered out of date, misleading, and/or offensive. Even the meaning of words such as ‘disability’, which usually refers to the social barriers that limit activities for disabled people, and ‘impairment’, which normally refers to the permanent mental/physical condition itself, have evolved considerably over time. It is important for historians to appreciate what terms were used for a given community in whichever specific time period they are studying. This should be done to avoid coming to anachronistic and inaccurate assessments about the past.

I have needed to consider this matter in my own PhD thesis, which focuses on the depiction of physical impairment in medieval Irish learned literature. While there were many labels for individual impairments, no single all-encompassing term seems to have existed for ‘disability’ in the medieval period (Metzler, 2006). For this blog, I would like to discuss some of the early Irish and Latin terms used for disability and impairment in medieval Irish sources. I hope this case study demonstrates some of the ways that conceptions about disability and impairment have varied across time, and how this must be considered when conducting a historical study.

In early Irish language, some terms refer to disability or impairment, but not always both. For example, dimbúa(i)d has been translated as ‘disability’ and can refer to defeat, disgrace, and misfortune. In contrast, ainim, béim, and céo can refer to forms of physical blemish or disfigurement. In fact léiniud, which has sometimes been translated as ‘impairment’, can refer to physical injury, harm or hinderance. That there are multiple, specific early Irish terms which appear to differentiate between a social barrier ‘disability’ and a physical affliction ‘impairment’ might suggest there was a distinction between these two concepts in medieval Ireland.

There are other words in early Irish where the links between disability and impairment are clearer. The term turbród, which more generally means ‘crushing, destroying’, can also have a legal application which refers to a married woman disabled by illness. The fact this word is used in legal contexts indicates an understanding in medieval Ireland that impairment could result in disability. There is other evidence to suggest that this idea existed in medieval Irish law. Social status could be affected based on what type of wound a person acquired, whilst certain physical and mental impairments lead to limits on legal rights and responsibilities (Kelly, 2016: 91-95; Plummer: 1921–1923, 37-38). It would seem that concepts of disability and impairment did exist, even if these exact words are not always used.

While the above terms might refer to general examples of disability or impairment, others can be more specific. The terms used for eye impairments are extensive and varied. Dall primarily means ‘blind totally in both eyes’, while the terms cáech and goll mean ‘blind in one of the two eyes’. Cáech comes from the Latin term for ‘blind’ (caecus) but in early Irish, the word specifically developed into the meaning ‘blind in one eye’ or ‘dim-sighted’. The concept of being blind in just one eye is also indicated with Irish compounds that combine leth ‘half, one of two’ óen/oín ‘one’ and túath ‘left’, with cáech and goll or rosc and súil (which both mean eye). This phenomenon can be seen in terms like lethshúilech ‘one-eyed’ and túathcháech, which has generally been translated as ‘blind in the left eye’. Leth is sometimes used to avoid ambiguity. Siobhán Barrett has also mentioned the term cláen ‘squint’ which is used in the saga Fled Dúin na nGéd, and cáech, which she implies could actually refer to total blindness (Barrett, 2019). There are some specific Latin terms for eye impairment which are found in the medieval Irish corpus, such as ceco a natiuitate, which is found in Vita Sancti Coemgeni ‘The Life of St Cóemgen’ and can be translated as ‘blind from birth’.

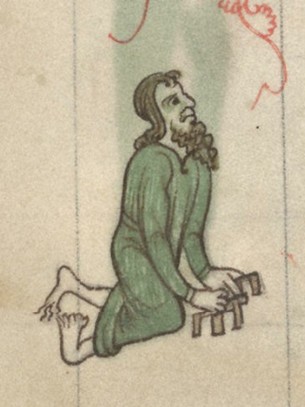

There are also numerous terms in early Irish language for specific limb impairments. The term mainchín refers to a person maimed in the hand, while bacclám can be translated as ‘one-armed’. There is also the term gerrlámach ‘short-armed’. Similar to ocular impairments, there are examples where óen/oín is used as a prefix to refer to limb impairments affecting one side of the body, such as óenláim ‘one-handed’. The term marb (which usually refers to someone being dead) can also refer to being maimed or having a withered arm. The adjectives fann and losc can both refer to foot or leg injuries, and the first can specially refer to limping, amongst other things. Losc is sometimes translated as ‘lame’, and tends to refer to an impairment of the leg.

Some of the terms found in these texts can have an unclear meaning, and make them harder to categorise. For example, the term clárainech features in several medieval Irish saints’ lives. Lisa Bitel has suggested that there is some confusion in early Irish literature between cláireinech/clárainech,which is often translated as referring to a ‘flat’ or ‘tabled-faced’ condition) and clairínech/cláirínech which means ‘cripple’, possibly caused by scribal error and/or literary imagination. From this, Bitel doubts it refers to the existence of a real-life condition (Bitel, 1990: 177). I disagree with this argument for several reasons. eDIL also states that clárainech is derived from enech, meaning ‘face’, and can be associated with the term dall, mentioned above, which means ‘blind’. These associations suggest that clárainech refers to someone having a specific condition, and was not just a term for ‘crippled’. Indeed, Clárainech is also defined in eDIL as ‘flat-faced (as a result of leprosy?)… born without nose or eyes visible’, and this is the meaning most often ascribed in the translations of the saints’ lives that I have examined in my own research. Furthermore, there are references in these stories to the healing of the eyes and noses, which indicate that they are referring to a specific facial disfigurement or impairment (see Betha Brigte: 82– 83). It is difficult to diagnose a term like clárainech with modern medical terminology without the risk of historical anachronism, and this reflects one of the many challenges about discussing disability in different historical contexts.

To conclude this brief summary of some of the language used for disability and impairment in medieval Ireland, we can already see some of the differences between our own ideas surrounding these concepts and those of the medieval era. It can be difficult to impose our own ideas upon vastly different cultures and time periods, and for this reason terms like ‘disability’ and ‘impairment’ should be used with great caution. I think there is some merit to using such words for the sake of communication and to convey how such ideas have varied over time. Thinking about disability this way helps us to re-consider our own conceptions of this term, and hopefully helps to increase our understanding of past societies and our own. These are some of the ideas that I hope to consider in my future research.

NB – This research was funded by the Research Ireland-funded Language, Education and Medical Learning in the Premodern Gaelic World (LEIGHEAS) project at Maynooth University, led by Deborah Hayden.

References and further reading

Barrett, Siobhán, ‘Varia I. The king of Dál nAraidi’s salve’, Ériu, 69 (2019), 171–178.

Betha Brigte, ed. and trans. by Whitley Stokes, in Whitley Stokes (ed.), Three Middle-Irish Homilies on the Lives of Saints Patrick, Brigit and Columba (Calcutta, 1877), pp. 50–87.

Bitel, Lisa M., Isle of the Saints: Monastic Settlement and Christian Community in Early Ireland (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1990).

Borsje, Jacqueline, The Celtic Evil Eye and Related Mythological Motifs in Medieval Ireland (Louvain: Peeters Publishers, 2012).

Boyd, Matthieu, ‘Modeling Impairment and Disability in Early Irish Literature’, Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, 2022, 41 (2022), 35–82.

Kelly, Fergus, A Guide to Early Irish Law, Rev. edn (Dublin: DIAS, 2016).

Mac Mathúna, Liam, ‘On the Expression and Concept of Blindness in Irish’, Studia Hibernica, 19 (1979), 26–62.

McLaughlin, Roisin, Early Irish Satire (Dublin: DIAS, 2008).

Metzler, Irina, Disability in Medieval Europe: Thinking about Physical Impairment during the High Middle Ages, c. 1100–1400 (London and New York: Routledge, 2006).

Ó Riain, Pádraig, A Dictionary of Irish Saints, (Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2011).

Plummer, Charles, ‘Notes on some Passages in the Brehon Laws II’, Ériu, 9 (1921–1923), 31–42.

Skinner, Patricia, Living with Disfigurement in Early Medieval Europe (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017).

Vita Sancti Coemgeni abbatis de Glenn da Loch , ed. by Charles Plummer, in Plummer, Charles, ed., Vitae Sanctorum Hiberniae, partim hactenus ineditae Volume 1 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1910), pp. 234–57.

Wheatley, Edward, Stumbling Blocks before the Blind: Medieval Constructions of a Disability (Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 2010).

Published: 25 Sept 2025 Categories: Emerging Scholars