On March 18th, as Covid-19 spread across the United States, Donald Trump declared himself a “wartime president”. Like many of his fellow leaders, he opted for metaphor amidst the crisis, enhancing his status while underscoring the severity of the situation. The pandemic has proved a fruitful ground for figurative language, with metaphors, similes, and other comparisons defining our relationship to a complex and tragic reality. Politicians have not been slow to exploit this resource, but the sheer density of images requires some comment and consideration.

War provided an organising image from the start, surfacing in speeches by Trump, Emanuel Macron, and Boris Johnson. Trump identified the virus as the “invisible enemy”, combatted (ostensibly) with military resolve. In a press conference only last week, Matt Hancock, the erstwhile UK Health Secretary, repeated the theme, commenting that “history has shown that understanding an enemy is essential to defeating it”, and recommitting to “this fight against our common foe”. Critiques of the language of war have surfaced from different sources, but there is more to it than just self-aggrandisement. War suspends ordinary life, it requires the energy and dedication of the society as a whole, and it sees the state at its most active, entitled to impose a lockdown, declare an emergency, and to borrow unprecedented amounts to fund its needs. It is an occasion for the heroic. Wars can also be won, and victory over enemies declared, a scenario that coronavirus unfortunately does not lend itself to.

Nor do politicians exercise any kind of monopoly here. The tendency to configure the predicament as a battle has been widespread, even in common speech. Doctors, nurses, and hospital workers fighting the disease have been identified as occupying the front line, along with others in support capacities (cleaners, supermarket workers, delivery people). The image confirms the essential nature of their contribution (even without adequate protective gear required for such a fight).

In the UK, Boris Johnson – a former columnist, with writerly inclinations – has shown a penchant for metaphor during the crisis. When he returned from his hospitalisation following infection by Covid-19, he made a public address in front of No. 10 by offering the somewhat predictable claim that “We are now beginning to turn the tide”, without recognising the unfortunate fact that tides have a habit of coming back in again. He went on to draw the following comparison:

If this virus were a physical assailant, an unexpected and invisible mugger, which I can tell you from personal experience it is, then this is the moment we have begun together to wrestle it to the floor.

Johnson cast himself in the role of victim – an innocent bystander who did not invite his fate with rash behaviour – assaulted by an unseen aggressor. Perhaps this was the only way to communicate vulnerability without dilating on the horrors of the disease or admitting culpability given his habit of doling out handshakes at a rugby match in the lead up to his illness.

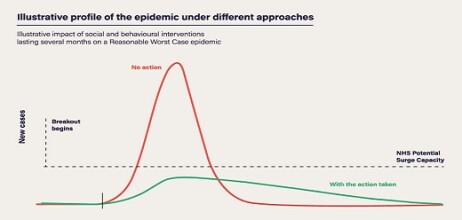

Johnson’s next contribution came when he resumed attendance at the daily press conference on April 30th. In his opening remarks, he declared: “We are past the peak, and we are on the downward slope.” No marks for originality here, but an apter image to the tidal metaphor under the circumstances. He then went on to add some baroque flourishes:

We’ve come through the peak, or rather we have come under what could have been a vast peak, as though we have been going through some huge alpine tunnel. And we can now see sunlight and the pasture ahead of us, and so it is vital that we do not now lose control and run slap into a second and even bigger mountain.

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/our-plan-to-rebuild-the-uk-governments-covid-19-recovery-strategy/our-plan-to-rebuild-the-uk-governments-covid-19-recovery-strategy).

Published: 26 May 2020 Categories: Covid-19 and the Humanities