Visual and Material Culture

Desert Island Dress: The Stories Behind the Clothes We Wear

Published: 8 Dec 2025

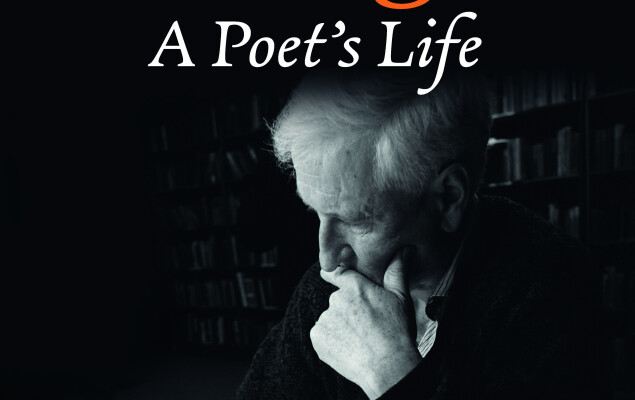

Irish Literature

Adrian Frazier, John Montague: A Poet’s Life (Lilliput, 2024)

Published: 26 Nov 2025

Event review

Feeding the Soul: Transnational Narratives of Food and Belonging

Published: 11 Nov 2025

Digital Humanities

Is the Irish Research community “ready” for Open Research practices and Responsible Research Assessment?

Published: 16 Oct 2025

Emerging Scholars

The Good, The Bad, and The Blemished: Disability Terminology in Medieval Ireland

Published: 25 Sept 2025

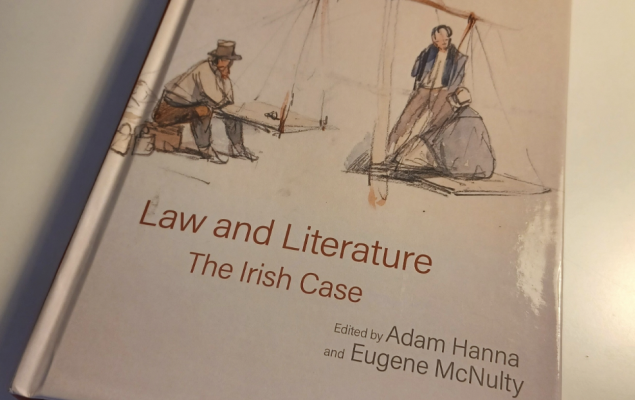

Legal Humanities

Antigone and Ireland at the Peacock Theatre: Event overview

Published: 17 Jun 2025

Legal Humanities

The Legal Humanities Working Group: An Introduction

Published: 25 Feb 2025

Born to Belong: The Origins and Impacts of US Birthright Citizenship

Published: 13 Feb 2025

The Green Credentials of the Wicked Witch of the West: An Ecocritical Perspective on Wicked (2024)

Published: 9 Dec 2024

Exhibiting Bad Bridget

Published: 16 Sept 2024